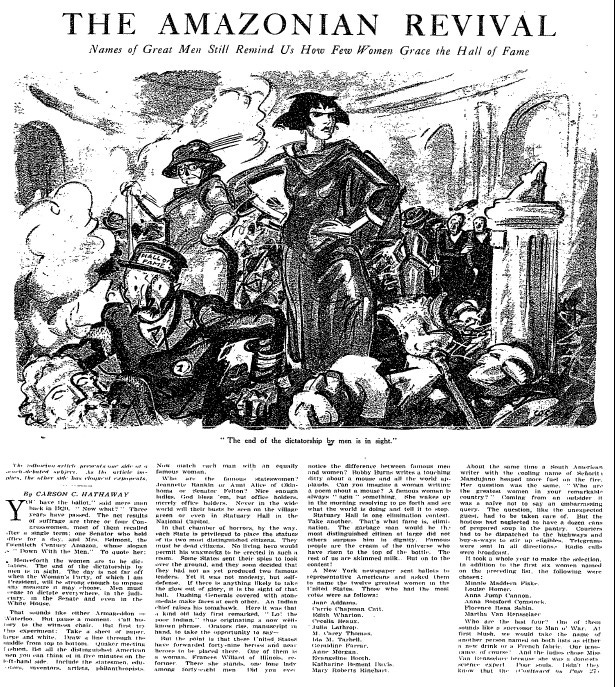

The Amazonian Revival: Names of Great Men Still Remind Us How Few Women Grace the Hall of Fame

A 1923 New York Times Magazine article predicted Jeannette Rankin would "never" be selected for the U.S. Capitol Building's National Statuary Hall. Her statue would ultimately be added in 1985.

Carson C. Hathaway's 1923 thesis: as of that year, no women had reached the levels of America's most successful men — whether in the realms of "statesmen, educators, investors, artists, [or] philanthropists." He listed the top contenders in that first category:

"Who are the famous stateswomen? Jeannette Rankin or Aunt Alice of Oklahoma or Senator Felton? Nice enough ladies, God bless 'em, but office holders, merely office holders. Never in the wide world will their busts be seen on the village green or even in Statuary Hall in the National Capitol."

Each state is granted two statues for National Statuary Hall, depicting great citizens from that state's history. The 1923 article noted that only one woman was depicted at the time. Today, women comprise 12 of the 100 statues — and soon to be 13.

Jeannette Rankin for Montana. Surely her subsequent election back to the House in 1940 helped her case for admission; as of the 1923 article, she'd served only a single two-year term but didn't seek reelection.

Frances Willard for Illinois, the first woman college president to confer degrees. Her statue was erected in 1905, making her the lone female statue as of the 1923 article's publication.

Willa Cather for Nebraska, author of novels including 1913's O Pioneers!, 1918's My Ántonia, and 1922's Pulitzer Prize winner One of Ours. Her statue was added earlier this year, in June 2023, replacing Agriculture Secretary and slavery supporter J. Sterling Morton.

Mary McLeod Bethune for Florida, founder of the historically black college now known as Bethune-Cookman University. Her statue was added last year, in 2022, replacing Confederate Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith.

Helen Keller for Alabama, the deaf and blind woman who advocated for education and women's suffrage. Her statue was added in 2009, replacing Alabama congressman and Confederate Army officer Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry.

Sacagawea for North Dakota, the Native American guide and translator for Lewis and Clark as they explored and mapped the American West.

Amelia Earhart for Kansas, the aviation pioneer and first woman to fly across the Atlantic Ocean.

Sarah Winnemucca for Nevada, the first Native American woman to publish a book: 1883's Life among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims.

Esther Hobart Morris for Wyoming, the first American woman to hold judicial office, appointed justice of the peace for the state's South Pass district in 1870.

Florence Sabin for Colorado, the first American woman medical school professor, who became a professor of histology (the microscopic study of tissues) in 1917.

Maria Sanford for Minnesota, an educator and one of the first American women college professors, teaching rhetoric at University of Minnesota.

Mother Joseph for Washington state, a humanitarian who opened a number of hospitals, orphanages, and schools.

Barbara Rose Johns for Virginia, a black teenage girl who protested school segregation in the early 1950s. Her forthcoming statue will replace Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, whose statue was removed in 2020.

Who were those three women Hathaway mentioned as the most prominent female politicians circa 1923?

In 1916, Rankin became the first woman elected to the House, from Montana.

In 1920, Alice Robertson became the second, from Oklahoma.

In 1922, Rebecca Latimer Felton became the first woman to serve in the Senate, from Georgia. The essentially symbolic one-day appointment temporarily filled a vacancy caused by an incumbent's death.

The Amazonian Revival

Published: Sunday, August 26, 1923